The following are 30 code examples for showing how to use markdown.markdown.These examples are extracted from open source projects. You can vote up the ones you like or vote down the ones you don't like, and go to the original project or source file by following the links above each example. Markdown Syntax Examples Block Elements. Creating paragraphs and new lines (or line breaks) are similar, but have subtle differences. There are quite a few different ways to create links, each of which depends on the meta-data you need. If you ever need to use. Standard Markdown doesn’t offer anything beyond this, but it’s very common for websites to need width, height, and CSS class attributes as well. The rest of this post is dedicated to various solutions to these shortcomings. To motivate this discussion, I’ll use the example of a large image that should be displayed at a smaller size. For example, Markdown plugins exist for every major blogging platform. While Markdown is a minimal markup language and is read and edited with a normal text editor, there are specially designed editors that preview the files with styles, which are available for all major platforms. A markdown example shows how to write a markdown file. This document integrates core syntax and extensions (GMF).

- Markdown Examples Python

- Markdown Example In Real Life

- R Markdown Example

- Markdown Example File

- Markdown Math Example

Markdown is a convenient HTML-focused shorthand syntax for formatting content such as documentation and blog articles, but it lacks basic features for image formatting, such as alignment and sizing.This post presents a variety of ways to format images with Markdown, from brute force to proprietary syntax extensions, unwise hacks, and everything in between.

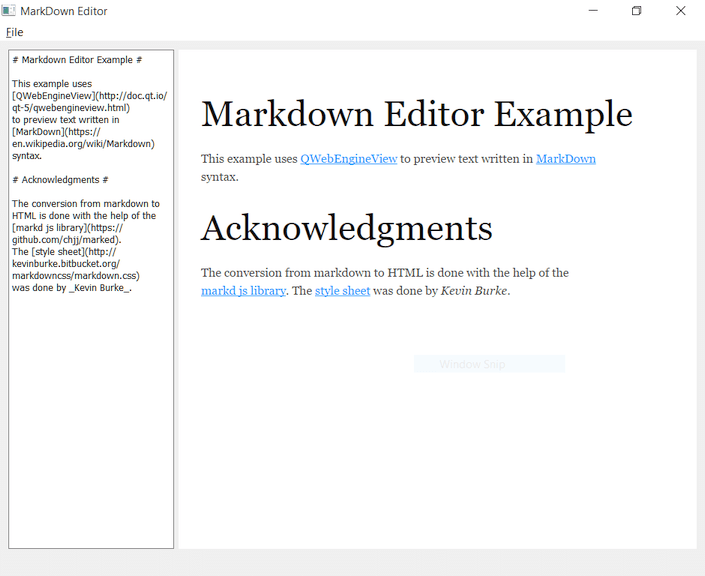

Here’s how you insert an image in Markdown:

That is, Markdown allows you to specify an <img> tag with src, alt, and title attributes in HTML.Standard Markdown doesn’t offer anything beyond this, but it’s very common for websites to need width, height, and CSS class attributes as well.

The rest of this post is dedicated to various solutions to these shortcomings.To motivate this discussion, I’ll use the example of a large image that should be displayed at a smaller size. Smart for mac download.

For example,

I won’t show you how to add alignment, floating, or padding—but my sizing example will suffice, because once you know how to change an image’s size, you’ll know how to do other things too.I’ll show you the best solutions first, and the undesirable ones last.

Use Standard HTML

Markdown was originally designed for HTML authoring, and permits raw HTML anywhere, anytime.As such, the most straightforward solution is simply to use HTML with the desired attributes:

This works, and gives you unrestrained control over the resulting HTML.But Markdown is appealing for its simplicity, unlike HTML that’s cluttered with messy markup.Thus, many people dislike this solution because it defeats the purpose of Markdown.

Use CSS And Special URL Parameters

In general, the best way to style images is with CSS.Modern CSS syntax can select elements based on the values of their attributes, so one way to apply CSS rules is to encode extra information into Markdown’s standard src attribute.In this section I’ll discuss these possibilities.Later I’ll show you some undesirable CSS-related techniques too.

There are two places in a URL that you can overload to carry information that CSS can use: the URL fragment, and URL query parameters.

The URL fragment is the part that comes after the # character.When it’s used in a website’s URL, it can scroll the page to bring a desired part of the content into view, but you can add it to images, too.When you do that, it essentially does nothing as far as the browser is concerned, and a typical user will never see it in the browser’s address bar either.But it’s useful for our styling needs.Here we’ll add a thumbnail fragment to the image’s source URL:

This information is kept entirely client-side, and browsers don’t transmit this part of the URL to the server when they request content.However, CSS and JavaScript can read the fragment and use it.Here’s how to write a CSS selector that will match images with this “thumbnail” information in the URL:

The *= selector syntax matches if #thumbnail appears anywhere in the src attribute.You could also anchor the matching to the end of the URL with $='#thumbnail'.

This permits encoding only a single value into the URL, but you can modify this technique to add several.CSS also has a ~= selector, which matches if the specified value appears exactly in the attribute’s value, as a space-delimited “word,” so to speak.This lets you simulate combining multiple “classes” in the URL fragment:

Now you can target these pseudo “class” names from CSS:

An equivalent way to encode a space into a URL is with the %20 URL encoding, but I’ve found that this doesn’t work1 in the Blackfriday Markdown processor with the technique I showed here:

Naturally, you can pick different ways to structure values, such as using a key=value syntax or whatever suits your purposes.Depending on what you prefer, you can use any of the CSS selector syntaxes that works well for you.

Another alternative is to use ordinary URL query parameters, the part that comes after the question-mark:

This will work, and you can use the same types of CSS selectors to apply styling to the resulting image.

However, in my opinion this is slightly less desirable, because query parameters are meant to transmit information to the server.The browser will include the parameters in the request, and there could be other disadvantages, such as preventing the browser from caching the images for better performance.Overall I don’t see any advantages to query parameters, unless there’s some reason you can’t use the URL fragment.

Use CSS’s nth-child() Selectors

Markdown Examples Python

You can also use CSS selectors that will select images based on their position in the document.For example, if your blog’s main content is wrapped inside an article element, and you want to change the appearance of the image inside the third paragraph, you could write the following CSS:

This will work, but it’s tedious and requires article-specific <style> tags with custom CSS.And you’ll need to change the CSS if you change the article, for example adding another paragraph above the image.In general this technique will be a burden to maintain, and I don’t do it.

To learn more about this, take a look at the CSS nth-of-type and nth-child selectors.

Use Proprietary Markdown Extensions

The original Markdown spec isn’t formal, and implementations vary.Many Markdown processors extend the syntax to add richness and control to the output.From Pandoc to Kramdown and Github-Flavored Markdown (GFM), extra syntaxes abound.There’s very little standardization, except for some consensus towards CommonMark and the gravitational pull of very popular libraries and processors.In this section I’ll explore some of these.

Some Markdown editors like Mou (a Mac writing app) have sizing extensions:

This example syntax is limited and isn’t widely supported.More common is the way Kramdown offers extensions to add attributes to block-level elements, including not only the height and width but CSS and other attributes:

Kramdown also supports one or more CSS classes with a shorthand syntax.Here’s an example of how to add class='thumbnail bordered' to the HTML after processing with Kramdown:

Pandoc offers a relative width specification, which works not only for HTML output, but for other output formats such as ( LaTeX ) as well:

Some other Markdown flavors offer similar ways to add attributes, though the syntax may differ slightly.All of these, however, extend the basic Markdown syntax in ways that may be incompatible.And some rumored support for extended syntax simply doesn’t exist; for example, I’ve seen references to nonexistent extensions in the blackfriday Markdown processor, which Hugo uses.

Use Wrapper HTML Tags

Another technique is to put an HTML tag around the <img> tag, like this:

Unfortunately, standard Markdown doesn’t process and convert the text inside of tags such as the <div>; as soon as it sees raw HTML it simply outputs it verbatim until the tags are closed again.This approach will work only with processors that support Markdown syntax extensions such as Markdown Extra.In Hugo, using Blackfriday, the resulting output is simply

Markdown Example In Real Life

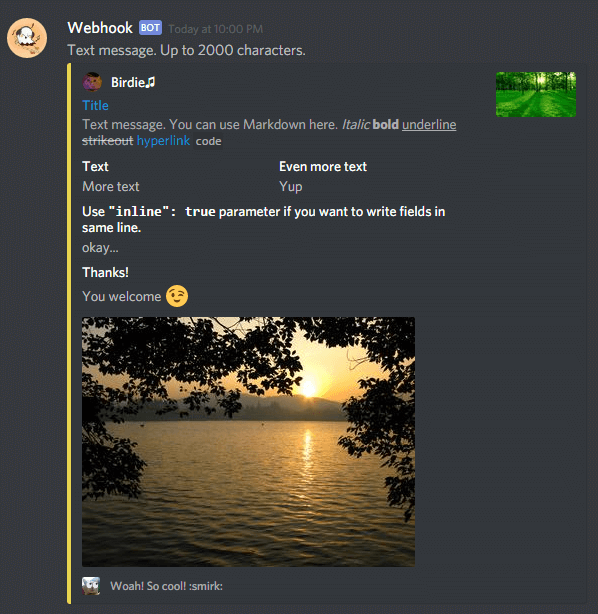

Use Processor Hacks That Markdown Editors Ignore

Some users like to edit in a WYSIWYG editor such as Mou, but use a system such as Hugo to render the final Markdown into HTML for publication.Hugo has special processors that can add features to the output, such as brace-delimited shortcodes, which Mou doesn’t understand.

You can take advantage of this to inject content that overflows the alt attribute.The trick is to make the shortcode output an extra closing quote at the beginning of its output, emit the desired HTML attributes but omit the closing quote, and let the Markdown processor supply that.The benefit is that your editor will ignore the markup it doesn’t recognize, so it doesn’t disrupt your editing workflow.I don’t think this is better than the alternatives myself, but I mention it for completeness.

Abuse Image Attributes As CSS Selector Targets

In addition to the URL fragment as discussed previously, modern CSS syntax can select values of the alt and title attributes that standard Markdown supports.In this section I’ll discuss each of these possibilities, although I discourage their use.

Many Markdown users are only aware of the standard syntax’s support for the alt attribute, and don’t add titles to their images.In fact, many don’t even add alt text:

This makes it seem as though the alt text is undeveloped real estate that could be repurposed, for example adding the pseudo-equivalent of a “thumbnail” CSS class.Here’s how you might attempt to do that:

The corresponding CSS to select and format this image could be

Technically, this will work, but it’s not good for accessibility.Users who are using a screen reader or other accessibility aid will gain no benefit, and will suffer due to the lack of helpful information and the presence of misleading data in places it’s not intended to be.I discourage this practice.

A variation I’ve seen is to append, rather than replace, the alt text, using syntaxes such as the following examples:

Those examples can be paired with a CSS selector that matches the end of the attribute, such as img[alt$='-thumbnail'].These are perhaps less offensive than replacing the alt text entirely, but I still discourage this because there are better ways.

A variant of this approach, which has a roughly equivalent impact on accessibility, is to overload the title attribute with formatting instructions:

This can be selected from CSS as follows:

Again, I want to emphasize that this approach is not better than misusing the alt attribute.You should use URL fragments or URL query parameters as discussed earlier, instead of hijacking the image’s alt text or title.

On the other hand, if you want to write custom CSS per-article and use the CSS selector to target the image’s real alt text or title, that’s perfectly fine.In fact this is probably easier to maintain than nth-child selectors:

The demos in this page use the actual markup in the code listings. You can viewthe page source or look at the file in my Github repoto see the original markup in HTML and/or Markdown formats.

- Thanks to a reader who pointed out that Markdown implementations vary widely in how they encode or interpret spaces. The technique as shown in this article doesn’t work with Grav, which needs spaces encoded as

%20. This thread on StackOverflow has more information. [return]

Markdown is probably the most commonly-used plain text markup used online, and is easy to get started with. The specific flavor of Markdown that Rippledoc uses is Pandoc-Markdown. Here’s a quick example of some pandoc-markdown -formatted text: first as the source you’d put into your file, then rendered as html.

And here’s that text rendered as html:

Paragraphs are separated by a blank line.

2nd paragraph. Italic, bold, and monospace. Itemized lists look like:

- this one

- that one

- the other one

Note that — not considering the asterisk — the actual text content starts at 4-columns in.

Block quotes are written like so.

They can span multiple paragraphs, if you like.

Use 3 dashes for an em-dash. Use 2 dashes for ranges (ex., “it’s all in chapters 12–14”). Three dots … will be converted to an ellipsis. Unicode is supported. ☺

An h2 header

Here’s a numbered list:

- first item

- second item

- third item

Note again how the actual text starts at 4 columns in (4 characters from the left side). Here’s a code sample:

As you probably guessed, indented 4 spaces. By the way, instead of indenting the block, you can use delimited blocks, if you like:

(which makes copying & pasting easier). You can optionally mark the delimited block for Pandoc to syntax highlight it:

An h3 header

Now a nested list: 365 o.

First, get these ingredients:

- carrots

- celery

- lentils

Boil some water.

Dump everything in the pot and follow this algorithm:

Do not bump wooden spoon or it will fall.

Notice again how text always lines up on 4-space indents (including that last line which continues item 3 above).

Here’s a link to a website, to a local doc, and to a section heading in the current doc. Here’s a footnote 1.

Tables can look like this:

| Name | Size | Material | Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Business | 9 | leather | brown |

| Roundabout | 10 | hemp canvas | natural |

| Cinderella | 11 | glass | transparent |

(The above is the caption for the table.) Pandoc also supports multi-line tables:

R Markdown Example

| Keyword | Text |

|---|---|

| red | Sunsets, apples, and other red or reddish things. |

| green | Leaves, grass, frogs and other things it’s not easy being. |

A horizontal rule follows.

Here’s a definition list:

- apples

- Good for making applesauce.

- oranges

- Citrus!

- tomatoes

- There’s no “e” in tomatoe.

Again, text is indented 4 spaces. (Put a blank line between each term and its definition to spread things out more.)

Here’s a “line block” (note how whitespace is honored):

Line too

Line tree

Markdown Example File

and images can be specified like so:

Inline math equation: (omega = dphi / dt). Display math should get its own line like so:

[I = int rho R^{2} dV]

And note that you can backslash-escape any punctuation characters which you wish to be displayed literally, ex.: `foo`, *bar*, etc.

Pandoc also allows you to do a few more things besides. You can read more about that in the Pandoc Manual.

Markdown Math Example

Some footnote text.↩